Sunday, February 29, 2004

Guns, Trauma, and Time

I just listened to tonight's episode of This American Life on public radio. The show featured interviews with two people who had been victims of horrible gun violence. One was a woman from Texas whose parents had been shot when a psychotic gunman opened fire in a restaurant. The other was a black police officer who had been shot repeatedly in the chest while sitting in a patrol car with his partner.

The woman had not been armed at the time. She had left her gun in her car, as required at the time by Texas law. She had thus been unable to defend her family from the gunman. She went on to become a leading advocate for a Texas law allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons. The law passed, and the woman was elected to the Texas House.

The police officer had been (naturally) armed at the time. As he points out, his being armed did not protect him from his attacker. He has since gone on to become a leading proponent of gun control laws, and has given up his own weapons.

The stories of these two people caused me to reflect on the gun issue, and what I think is a fundamental philosophical difference between "conservatives" and "liberals," having to do with the nature of time and trauma.

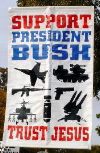

Conservatives are always presenting themselves as the clear-eyed realists who understand the nature of human evil in the world. They caricaturize liberals as foggy-headed romantics or idealists whose refusal to admit the capacity of humans for evil only contributes to more violence and inhibits societies from protecting themselves against it.

But (as you might guess) I see it the other way around. Conservatives are wounded people who have embarked on an entirely natural and understandable but quixotic and impossible effort to reverse time and re-stage the scene of their trauma--but this time with the power to defend themselves and thwart the trauma. As any reader of Freud knows, this instinct is ingrained in us, and is a cause of the repetitions and compulsions in our behavior through which we both seek to minimize our suffering, and ensure the continuation (and increase) of that suffering.

Conservatives suffer from the delusion that they can will these repetitions of past trauma--that they can crouch in wait with gun in hand for the killer to stalk once again into the restaurant--and this time they will be ready to blow his head off. This delusion seeks to create a sense of power by making fear permanent, and thus less threatening: the gun-holder awaits the image of the killer with gun in hand, an image from the past which will at any moment step out from the future, ready to kill, but now anticipated and thus contained, controlled and defeatable.

This fantasy really partakes of the same logic behind capital punishment, which tempts us with the fantasy of retribution--that we can re-stage (and overcome) the scene of trauma and violence, but with the roles reversed: ourselves as punishers, and the murderer as victim. This act will reverse the pain of time through a theatre of "justice," offering the semblance of a symmetry or balance of aggression and wounding that suggests fulfillment, the re-paying of a debt, temporal and moral closure.

Liberals, however, take the more realistic view about violence, evil, and the nature of time. Yes, evil exists; yes, violence bursts into our experience and creates trauma. But we (and I recognize the ambiguity of this "we") recognize that the essential nature of trauma (as of experience, flowing out of the future into our present) is that of surprise: it cannot be anticipated, just as time cannot be reversed and the past will not repeat itself according to the designs of our desires and imagining.

Not that we can't (like any good Boy Scout) "be prepared." Not that we can't be savvy and smart. Not that we can't even (should we so choose) arm ourselves with weapons. But we understand that the thing we are preparing for and arming ourselves against will not and cannot be the thing which caused the fear that made us arm ourselves in the first place. The killer will not be the same killer. The old killer has done his work--work that can addressed in all kinds of different ways, but cannot be reversed or obliterated.

And available to us is a more empowering protective stance arising from a more realistic (i.e., more humble) view of the future. We can't see the future, and we can have the wisdom to know that when it comes it won't take the shape we expected it to. What we can do is conceive of futures different from (and preferable to) the past, and assist in (though not determine) their creation by open-mindedly equipping ourselves for them.

Thus the thinking of that police officer. He knows that no matter how he crouches in wait with gun in hand, he can never be prepared for the moment when the killer reaches in the window and commences pumping bullets into his chest. He is also surely aware that no gun-control law or laws can ever prevent some other killer from arming himself and enacting more violence. There will always be people ready and able to kill indiscriminately. But he (the police officer) can imagine a world in which there are fewer guns in fewer hands. Maybe--maybe--in such a world the violence that was perpetrated against him will be less likely to happen to someone else. He can't be certain of this: but what he can be certain of is that what did happen to him cannot be repeated, cannot be undone, cannot be made right. Unburdening himself of this malignant fantasy enables the police officer to face the future with mourning, with regret, with the after-effects of trauma, but with hope. Hope is empowering. Wise humility is empowering. But delusions of power--over violence, over trauma, over time--can only come to no good.

The woman had not been armed at the time. She had left her gun in her car, as required at the time by Texas law. She had thus been unable to defend her family from the gunman. She went on to become a leading advocate for a Texas law allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons. The law passed, and the woman was elected to the Texas House.

The police officer had been (naturally) armed at the time. As he points out, his being armed did not protect him from his attacker. He has since gone on to become a leading proponent of gun control laws, and has given up his own weapons.

The stories of these two people caused me to reflect on the gun issue, and what I think is a fundamental philosophical difference between "conservatives" and "liberals," having to do with the nature of time and trauma.

Conservatives are always presenting themselves as the clear-eyed realists who understand the nature of human evil in the world. They caricaturize liberals as foggy-headed romantics or idealists whose refusal to admit the capacity of humans for evil only contributes to more violence and inhibits societies from protecting themselves against it.

But (as you might guess) I see it the other way around. Conservatives are wounded people who have embarked on an entirely natural and understandable but quixotic and impossible effort to reverse time and re-stage the scene of their trauma--but this time with the power to defend themselves and thwart the trauma. As any reader of Freud knows, this instinct is ingrained in us, and is a cause of the repetitions and compulsions in our behavior through which we both seek to minimize our suffering, and ensure the continuation (and increase) of that suffering.

Conservatives suffer from the delusion that they can will these repetitions of past trauma--that they can crouch in wait with gun in hand for the killer to stalk once again into the restaurant--and this time they will be ready to blow his head off. This delusion seeks to create a sense of power by making fear permanent, and thus less threatening: the gun-holder awaits the image of the killer with gun in hand, an image from the past which will at any moment step out from the future, ready to kill, but now anticipated and thus contained, controlled and defeatable.

This fantasy really partakes of the same logic behind capital punishment, which tempts us with the fantasy of retribution--that we can re-stage (and overcome) the scene of trauma and violence, but with the roles reversed: ourselves as punishers, and the murderer as victim. This act will reverse the pain of time through a theatre of "justice," offering the semblance of a symmetry or balance of aggression and wounding that suggests fulfillment, the re-paying of a debt, temporal and moral closure.

Liberals, however, take the more realistic view about violence, evil, and the nature of time. Yes, evil exists; yes, violence bursts into our experience and creates trauma. But we (and I recognize the ambiguity of this "we") recognize that the essential nature of trauma (as of experience, flowing out of the future into our present) is that of surprise: it cannot be anticipated, just as time cannot be reversed and the past will not repeat itself according to the designs of our desires and imagining.

Not that we can't (like any good Boy Scout) "be prepared." Not that we can't be savvy and smart. Not that we can't even (should we so choose) arm ourselves with weapons. But we understand that the thing we are preparing for and arming ourselves against will not and cannot be the thing which caused the fear that made us arm ourselves in the first place. The killer will not be the same killer. The old killer has done his work--work that can addressed in all kinds of different ways, but cannot be reversed or obliterated.

And available to us is a more empowering protective stance arising from a more realistic (i.e., more humble) view of the future. We can't see the future, and we can have the wisdom to know that when it comes it won't take the shape we expected it to. What we can do is conceive of futures different from (and preferable to) the past, and assist in (though not determine) their creation by open-mindedly equipping ourselves for them.

Thus the thinking of that police officer. He knows that no matter how he crouches in wait with gun in hand, he can never be prepared for the moment when the killer reaches in the window and commences pumping bullets into his chest. He is also surely aware that no gun-control law or laws can ever prevent some other killer from arming himself and enacting more violence. There will always be people ready and able to kill indiscriminately. But he (the police officer) can imagine a world in which there are fewer guns in fewer hands. Maybe--maybe--in such a world the violence that was perpetrated against him will be less likely to happen to someone else. He can't be certain of this: but what he can be certain of is that what did happen to him cannot be repeated, cannot be undone, cannot be made right. Unburdening himself of this malignant fantasy enables the police officer to face the future with mourning, with regret, with the after-effects of trauma, but with hope. Hope is empowering. Wise humility is empowering. But delusions of power--over violence, over trauma, over time--can only come to no good.