Wednesday, June 08, 2005

Reclaiming Religious Language?

speakingcorpse writes:

Rowan Williams, the highly intelligent and humane Archbishop of Canterbury, offers in this 2002 lecture (delivered when he was still Archbishop of Wales) some useful points about the relation of religion and politics under the conditions of secular modernity.

Williams starts with the assumption that "secularization" is the dominant force in modern world history. Secularization is the removal of all "religious" talk from the public square ("religious" being applicable to any talk about VALUES that cannot be calculated, predicted, measured, and attributable to rational, self-interested agents). One of his main points is that fundamentalism is "secularized" religion; it reduces religion to a series of simple descriptive propositions about reality, to which one is asked to give simple assent for the sake of one's personal benefit.

The question of how one lives INTO religious language, endowing it with the bodily meaning of one's own suffering, is excluded from secularized/fundamentalist religion. It is excluded because this true invigoration of religious words takes, above all else, TIME. Fundamentalist religion is just one more way of denying the darkness, the near invisibility, of the meaning of the life and suffering of other people. It does not give the time it takes to apprehend this life.

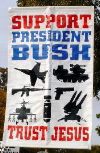

Fundamentalism is a way instead of imagining a fantastically transparent and pristine public order, purged of the depth and darkness of the human beings whose lives are the only source of that order's real dimensions.

One of the benefits of Williams' analysis is that it suggests how the homognization, corporatization, instrumentalization, and globalization of the human community can be resisted: through the purification of religious language. Religious language is a good place to start because it is already used by the increasingly dangerous (secularized) fundamentalists

who think (incorrectly, but by the million) that they are resisting the onslaught of secular mechanization and dehumanization to which they are actually submitting. Furthermore, religious language (no matter what the fanatics say) is constituted as such by its provisionality, its readiness to be, in part, discarded, and thus purified. For religious language claims to point toward something that is beyond its own scope of reference. So it demands and enacts self-skepticism; and it enacts that skepticism even when (especially when?) it claims for itself apocalyptic certainty.

The megachurches can try, just as the Roman Curia of the Renaissance tried, to deny that they are founded on the words of the gospel of Jesus. But the words remain, shaking the foundations:

"Being asked by the Pharisees when the kingdom of God was coming, he answered them, 'The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed; nor will they say, 'Lo, here it is!' or 'There!' for behold, the kingdom of God is in the midst of you" (Luke 20-21).

It is not coming with a grand and visible announcement that compels attention and obedience; it is here, among and between us, if we freely give it the attention it needs to become manifest. This sort of sustained, meditative, time-consuming attention is the antidote to secularism. It is often enough associated with aesthetic contemplation, but perhaps it is more essentially religious. Do we pay attention to certain things always out of a desire for pleasure? Or is our attention compelled by a need to obey a silent call?

In any case, certain words that describe this mode of attention are words that are already in use (without proper attention to their meaning) by millions of secularized religious persons. Perhaps it is through this thicket of confused religious language that a true leader might burn a path toward the center of the public square, where he could claim a new place for truth.

Rowan Williams, the highly intelligent and humane Archbishop of Canterbury, offers in this 2002 lecture (delivered when he was still Archbishop of Wales) some useful points about the relation of religion and politics under the conditions of secular modernity.

Williams starts with the assumption that "secularization" is the dominant force in modern world history. Secularization is the removal of all "religious" talk from the public square ("religious" being applicable to any talk about VALUES that cannot be calculated, predicted, measured, and attributable to rational, self-interested agents). One of his main points is that fundamentalism is "secularized" religion; it reduces religion to a series of simple descriptive propositions about reality, to which one is asked to give simple assent for the sake of one's personal benefit.

The question of how one lives INTO religious language, endowing it with the bodily meaning of one's own suffering, is excluded from secularized/fundamentalist religion. It is excluded because this true invigoration of religious words takes, above all else, TIME. Fundamentalist religion is just one more way of denying the darkness, the near invisibility, of the meaning of the life and suffering of other people. It does not give the time it takes to apprehend this life.

Fundamentalism is a way instead of imagining a fantastically transparent and pristine public order, purged of the depth and darkness of the human beings whose lives are the only source of that order's real dimensions.

One of the benefits of Williams' analysis is that it suggests how the homognization, corporatization, instrumentalization, and globalization of the human community can be resisted: through the purification of religious language. Religious language is a good place to start because it is already used by the increasingly dangerous (secularized) fundamentalists

who think (incorrectly, but by the million) that they are resisting the onslaught of secular mechanization and dehumanization to which they are actually submitting. Furthermore, religious language (no matter what the fanatics say) is constituted as such by its provisionality, its readiness to be, in part, discarded, and thus purified. For religious language claims to point toward something that is beyond its own scope of reference. So it demands and enacts self-skepticism; and it enacts that skepticism even when (especially when?) it claims for itself apocalyptic certainty.

The megachurches can try, just as the Roman Curia of the Renaissance tried, to deny that they are founded on the words of the gospel of Jesus. But the words remain, shaking the foundations:

"Being asked by the Pharisees when the kingdom of God was coming, he answered them, 'The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed; nor will they say, 'Lo, here it is!' or 'There!' for behold, the kingdom of God is in the midst of you" (Luke 20-21).

It is not coming with a grand and visible announcement that compels attention and obedience; it is here, among and between us, if we freely give it the attention it needs to become manifest. This sort of sustained, meditative, time-consuming attention is the antidote to secularism. It is often enough associated with aesthetic contemplation, but perhaps it is more essentially religious. Do we pay attention to certain things always out of a desire for pleasure? Or is our attention compelled by a need to obey a silent call?

In any case, certain words that describe this mode of attention are words that are already in use (without proper attention to their meaning) by millions of secularized religious persons. Perhaps it is through this thicket of confused religious language that a true leader might burn a path toward the center of the public square, where he could claim a new place for truth.