Tuesday, January 29, 2008

clues

I've been pondering the attraction of the Unity/Hope/Change rhetoric of the Obama campaign that seems to have flaked away the outer layer of even the crustiest Mencken wannabes in our commentariat. Usually I don't get very far in these musings because the lack of content doesn't give one much to work with. At the same time the tropes strike me as fascistically sinister in their emptiness, so my mind involuntarily wanders into less creepy pastures. Privileged scions raping the planet is nothing new. The dimmest hint of our First! Black! President! bringing us all together for a Lethe-flavored Kool-Aid quaff followed by a unanimous glassy-eyed march into the Hellmouth opens up whole new vistas of nausea.

At this point, the fantasia of the immolation of the Right has gotten me through so many nights that the idea of "unity" not only doesn't strike me as possible, it doesn't seem remotely desirable. What kind of mush-headed masochistic feeb wants to let bygones be bygones at this point? How thick does your myopia have to be that you're ascribing our national malaise to an amorphously uncomfortable sense of "dividedness". Since when is being divided from malevolent bastards not a virtue? You'd think such an infantilized populace would at least have enough of a sense of stubborn adolescent pride to put a veneer of bravado over the anxiety they feel at watching Mommy and Daddy fight.

Don't get me wrong. I'm right there with everyone else on the overwhelming sense of self-loathing after a drawn out auto-degradation binge. As a nation we've been fucking too many of the wrong people and blowing too many laxative-cut lines for too long. The Global Village is on its way to work and we're left to stumble home squinting at the morning light and trying to ignore the stares of approbation. Who wouldn't want a nice hot ethical bath and time to sleep it off? Who wouldn't like to be reminded of our better selves? It's just that our better selves never had much truck with 'bipartisanship' or 'reaching across the aisle'. Our better selves know that even if there's a reach-around it don't mean you're not getting fucked.

All this is to say that I really don't get it. So instead of my tortured metaphors, I submit for your reading pleasure someone who understands America much better than I could. I was surprised to find the essay had been posted online since I'd thought it was only in print. It is mainly an attempt to deal with the question that's been on every Proggie mind since the Bush coup: Why does the Right win? Looking at it with a year's distance, it may provide some clues as to why Obama appears to be turning it around.

the rest

At this point, the fantasia of the immolation of the Right has gotten me through so many nights that the idea of "unity" not only doesn't strike me as possible, it doesn't seem remotely desirable. What kind of mush-headed masochistic feeb wants to let bygones be bygones at this point? How thick does your myopia have to be that you're ascribing our national malaise to an amorphously uncomfortable sense of "dividedness". Since when is being divided from malevolent bastards not a virtue? You'd think such an infantilized populace would at least have enough of a sense of stubborn adolescent pride to put a veneer of bravado over the anxiety they feel at watching Mommy and Daddy fight.

Don't get me wrong. I'm right there with everyone else on the overwhelming sense of self-loathing after a drawn out auto-degradation binge. As a nation we've been fucking too many of the wrong people and blowing too many laxative-cut lines for too long. The Global Village is on its way to work and we're left to stumble home squinting at the morning light and trying to ignore the stares of approbation. Who wouldn't want a nice hot ethical bath and time to sleep it off? Who wouldn't like to be reminded of our better selves? It's just that our better selves never had much truck with 'bipartisanship' or 'reaching across the aisle'. Our better selves know that even if there's a reach-around it don't mean you're not getting fucked.

All this is to say that I really don't get it. So instead of my tortured metaphors, I submit for your reading pleasure someone who understands America much better than I could. I was surprised to find the essay had been posted online since I'd thought it was only in print. It is mainly an attempt to deal with the question that's been on every Proggie mind since the Bush coup: Why does the Right win? Looking at it with a year's distance, it may provide some clues as to why Obama appears to be turning it around.

Is it possible that America is actually a nation of frustrated altruists? Certainly this is not the way that we normally think about ourselves. Our normal habits of thought, actually, tend toward a rough and ready cynicism. The world is a giant marketplace; everyone is in it for a buck; if you want to understand why something happened, first ask who stands to gain by it. The same attitudes expressed in the back rooms of bars are echoed in the highest reaches of social science. America’s great contribution to the world in the latter respect hasbeen the development of “rational choice” theories, which proceed from the assumption that all human behavior can be understood as a matter of economic calculation, of rational actors trying to get as much as possible out of any given situation with the least cost to themselves. As a result, in most fields, the very existence of altruistic behavior is considered a kind of puzzle, and everyone from economists to evolutionary biologists has become famous through attempts to “solve” it–that is, to explain the mystery of why bees sacrifice themselves for hives or human beings hold open doors and give correct street directions to total strangers. At the same time, the case of the military bases suggests the possibility that in fact Americans, particularly the less affluent ones, are haunted by frustrated desires to do good in the world.

It would not be difficult to assemble evidence that this is the case. Studies of charitable giving, for example, have shown the poor tobe the most generous: the lower one’s income, the higher the proportion of it that one is likely to give away to strangers. The same pattern holds true, incidentally, when comparing the middle classes and the rich: one study of tax returns in 2003 concluded that if the most affluent families had given away as much of their assets as even the average middle-class family, overall charitable donations that year would have increased by $25 billion. (All this despite the fact that the wealthy have far more time and opportunity.) Moreover, charity represents only a tiny part of the picture. If one were to break down what typical American wage earners do with their disposable income, onewould find that they give much of it away, either through spending in one way or another on their children or through sharing with others: presents, trips, parties, the six-pack of beer for the local softball game. One might object that such sharing is more a reflection of the real nature of pleasure than anything else (who would want to eat a delicious meal at an expensive restaurant all by himself?), but this is actually half the point. Even our self-indulgences tend to be dominated by the logic of the gift. Similarly, some might object that shelling out a small fortune to send one’s children to an exclusive kindergarten is more about status than altruism. Perhaps: but if you look at what happens over the course of people’s actual lives, it soon becomes apparent that this kind of behavior fulfills an identical psychological need. How many youthful idealists throughout history have managed to finally come to terms with a world based on selfishness and greed the moment they start a family? If one were to assume altruism were the primary human motivation, this would make perfect sense: The only way they can convince themselves to abandon their desire to do right by the world as a whole is to substitute an even more powerful desire to do right by their children.

What all this suggests to me is that American society might well work completely differently than we tend to assume. Imagine, for a moment, that the United States as it exists today were the creation of some ingenious social engineer. What assumptions about human nature could we say this engineer must have been working with? Certainly nothing like rational choice theory. For clearly our social engineer understands that the only way to convince human beings to enter into the world of work and the marketplace (that is, of mind-numbing labor and cutthroat competition) is to dangle the prospect of thereby being able to lavish money on one’s children, buy drinks for one’s friends, and, if one hits the jackpot, spend the rest of one’s life endowing museums and providing AIDS medications to impoverished countries in Africa. Our theorists are constantly trying to strip away the veil of appearances and show how all such apparently selfless gestures really mask some kind of self-interested strategy, but in reality American society is better conceived as a battle over access to the right to behave altruistically. Selflessness–or, at least, the right to engage in high-minded activity–is not the strategy. It is the prize.

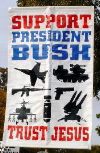

If nothing else, I think this helps us understand why the right has been so much better, in recent years, at playing to populist sentiments than the left. Essentially, they do it by accusing liberals of cutting ordinary Americans off from the right to do good in the world. Let me explain what I mean here by throwing out a series of propositions....

the rest