Monday, May 11, 2009

Man, knee

This started as a response to The Alchemist in the comments to my last post, but as I was writing I realized something interesting enough that I felt it deserved a post of its own. And plus I know, or hope, that we all love reading the Sports Guy, Bill Simmons.

Alchemist, I won't get into the vagaries of fandom, though from what I can tell those titles would have been a lot harder to get without Manny.

The part of this that I find so creepy is the way that one individual after another is isolated and destroyed, with the same drama of shock, outrage, and sacrifice played out again and again. Beyond its inherent inaccuracy-- we don't really have a picture of who was or wasn't, so it is not really fair to isolate cases and pretend that they are so much worse than the others-- it corresponds too closely to the way our culture processes fame in general, with this repeated trajectory from idolization to hateful destruction (or, in the case of women, fetishization/exploitation to induced self-destruction). By this logic, Alchemist, your stance toward Manny is less problematic-- if, as you say, you always hated him. But what if it comes out that Papi was also on steroids?

If baseball really wants to do something about steroids, and clean up the historical record, the answer would be -less- punishment, not more. There would have to be the creation of some real form of amnesty so that people could just admit what they did and move on. We all know that this will never happen.

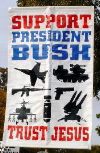

It is no coincidence that baseball, America's secular religion, is the ground on which this is all being played out. Only in baseball does it matter if the fans are being "betrayed," because no other sport has those stakes. People adore football, but no one would feel betrayed if it came to light that certain, or most, linebackers are roided up the wazoo. With the exceptions of a few QBs and receivers, football players are faceless soldiers. Whereas the baseball player, his cap on to mask loss of hair, eternally youthful, reaches back into some sort of imagined history. The Yankee's prohibition against facial hair captures this desire best: pre-1960s.

So what, exactly, is being betrayed by baseball heroes using steroids? The answer to this, I think, would give us great insight into the contemporary American male psyche.

In this light, the Sports Guy's column is a stroke of genius-- one of the best things he has ever written. He describes a hypothetical conversation at a Sox game on May 7, 2014 with his father and six year-old son, in which he is trying to explain to his son why it is okay that the 04 and 07 Red Sox might have been on PEDs. His father, enthusiastic and still happy that he lived to see a title, forgives/denies everything, exclaiming, "I'd do it again!" with glee. Simmons himself is caught between wanting his son to believe in the mythos of his favorite team and knowing that it might all be undermined by the truth of cheating. The son is insistently skeptical-- he can see the whole game. He points out the very real possibility that much of the team was on PEDs; his faith in the entire game is in danger, and he simply knows the '04 team as "the one that cheated." Here is one such exchange:

'My son tries to soak everything in. That's lot to process for a 6-year-old.

Finally ...

"So when the Red Sox won in 2004, did you know some of the guys might have been cheating?" he asks.

"At the time?" I answer. "No. Either we were in total denial, or we just didn't care."

"I'd do it again!" my dad yells happily, getting another withering glare from me.

"You have to understand," I say. "EVERYONE cheated back then. You know how I drive 80 on the highway even though all the signs say to go 55? That's how everyone thought back then -- the signs said one thing, but everyone did the other. There were so many people cheating that, competitively, you almost had to cheat to keep up with everyone else."

"So why didn't the people in charge get everyone to stop cheating?" my son asks.

"I wish I knew. The players' union didn't care, the commissioner's office didn't care, nobody cared. Until it was too late."'

At the end, the son comforts his dad with Simmons' own halfhearted refrain that "everyone was using back then."

The Sports Guy has split himself into three parts that correspond to a classic triad-- superego, ego, and id-- with the stunning reversal of correspondent Oedipal roles. Simmons' DAD is id, the shameless, dumb, eternally entertained fan, who is enviously free of the law; he could care less if they cheated-- the key is that they WON. While the SON, the child, is not repository of innocent yet obscene drives, but in fact superego, guardian of law and honesty, imposer of infinite guilt. Simmons-ego is helpless before the Law, caught between the rationalizations that only half-sustain his faith in baseball and the potential guilt of handing down a sham to his own progeny. There is no female figure here, no foil to a neverending chain of male inheritance-- and this is of course the appeal of all of Simmons' columns: sports are for men and their dads and their sons, history itself.

But the key is that at the end the son is able to utter the disavowal. Simmons cannot comfort himself; only his son/the Law can. But the Law the son speaks--the lie that one knows, but...--suddenly sounds just like the refrain that only grandpa, only id, can fully believe and enjoy. This is because id and superego, drives and law, share a nefarious common ground. Id is precisely the innocence that knows how to get what it wants, innocence with the wisdom of a crafty old coot. Superego comes from Papa, from parental authority, but it is idealized in our minds to the point of innocence: baseball, for example, must be utterly pure, a repository of all values sacred and American. The Law that insists that baseball be pure is precisely what ALLOWS us to a) enjoy the deception and b) sacrifice others so that the deception can continue.

Last point: has there ever been a greater metaphor for Phallus-- the authority that one WEARS, that one must put on, but never becomes-- than steroids, which render us falsely superhuman, garner total adoration, and literally in doing so destroy the body and guarantee a horrific future mortification in and by public?

Alchemist, I won't get into the vagaries of fandom, though from what I can tell those titles would have been a lot harder to get without Manny.

The part of this that I find so creepy is the way that one individual after another is isolated and destroyed, with the same drama of shock, outrage, and sacrifice played out again and again. Beyond its inherent inaccuracy-- we don't really have a picture of who was or wasn't, so it is not really fair to isolate cases and pretend that they are so much worse than the others-- it corresponds too closely to the way our culture processes fame in general, with this repeated trajectory from idolization to hateful destruction (or, in the case of women, fetishization/exploitation to induced self-destruction). By this logic, Alchemist, your stance toward Manny is less problematic-- if, as you say, you always hated him. But what if it comes out that Papi was also on steroids?

If baseball really wants to do something about steroids, and clean up the historical record, the answer would be -less- punishment, not more. There would have to be the creation of some real form of amnesty so that people could just admit what they did and move on. We all know that this will never happen.

It is no coincidence that baseball, America's secular religion, is the ground on which this is all being played out. Only in baseball does it matter if the fans are being "betrayed," because no other sport has those stakes. People adore football, but no one would feel betrayed if it came to light that certain, or most, linebackers are roided up the wazoo. With the exceptions of a few QBs and receivers, football players are faceless soldiers. Whereas the baseball player, his cap on to mask loss of hair, eternally youthful, reaches back into some sort of imagined history. The Yankee's prohibition against facial hair captures this desire best: pre-1960s.

So what, exactly, is being betrayed by baseball heroes using steroids? The answer to this, I think, would give us great insight into the contemporary American male psyche.

In this light, the Sports Guy's column is a stroke of genius-- one of the best things he has ever written. He describes a hypothetical conversation at a Sox game on May 7, 2014 with his father and six year-old son, in which he is trying to explain to his son why it is okay that the 04 and 07 Red Sox might have been on PEDs. His father, enthusiastic and still happy that he lived to see a title, forgives/denies everything, exclaiming, "I'd do it again!" with glee. Simmons himself is caught between wanting his son to believe in the mythos of his favorite team and knowing that it might all be undermined by the truth of cheating. The son is insistently skeptical-- he can see the whole game. He points out the very real possibility that much of the team was on PEDs; his faith in the entire game is in danger, and he simply knows the '04 team as "the one that cheated." Here is one such exchange:

'My son tries to soak everything in. That's lot to process for a 6-year-old.

Finally ...

"So when the Red Sox won in 2004, did you know some of the guys might have been cheating?" he asks.

"At the time?" I answer. "No. Either we were in total denial, or we just didn't care."

"I'd do it again!" my dad yells happily, getting another withering glare from me.

"You have to understand," I say. "EVERYONE cheated back then. You know how I drive 80 on the highway even though all the signs say to go 55? That's how everyone thought back then -- the signs said one thing, but everyone did the other. There were so many people cheating that, competitively, you almost had to cheat to keep up with everyone else."

"So why didn't the people in charge get everyone to stop cheating?" my son asks.

"I wish I knew. The players' union didn't care, the commissioner's office didn't care, nobody cared. Until it was too late."'

At the end, the son comforts his dad with Simmons' own halfhearted refrain that "everyone was using back then."

The Sports Guy has split himself into three parts that correspond to a classic triad-- superego, ego, and id-- with the stunning reversal of correspondent Oedipal roles. Simmons' DAD is id, the shameless, dumb, eternally entertained fan, who is enviously free of the law; he could care less if they cheated-- the key is that they WON. While the SON, the child, is not repository of innocent yet obscene drives, but in fact superego, guardian of law and honesty, imposer of infinite guilt. Simmons-ego is helpless before the Law, caught between the rationalizations that only half-sustain his faith in baseball and the potential guilt of handing down a sham to his own progeny. There is no female figure here, no foil to a neverending chain of male inheritance-- and this is of course the appeal of all of Simmons' columns: sports are for men and their dads and their sons, history itself.

But the key is that at the end the son is able to utter the disavowal. Simmons cannot comfort himself; only his son/the Law can. But the Law the son speaks--the lie that one knows, but...--suddenly sounds just like the refrain that only grandpa, only id, can fully believe and enjoy. This is because id and superego, drives and law, share a nefarious common ground. Id is precisely the innocence that knows how to get what it wants, innocence with the wisdom of a crafty old coot. Superego comes from Papa, from parental authority, but it is idealized in our minds to the point of innocence: baseball, for example, must be utterly pure, a repository of all values sacred and American. The Law that insists that baseball be pure is precisely what ALLOWS us to a) enjoy the deception and b) sacrifice others so that the deception can continue.

Last point: has there ever been a greater metaphor for Phallus-- the authority that one WEARS, that one must put on, but never becomes-- than steroids, which render us falsely superhuman, garner total adoration, and literally in doing so destroy the body and guarantee a horrific future mortification in and by public?