Saturday, June 18, 2005

...

We are approaching the point where it will become impossible to continue blogging items like this. Really, to post this without committing either suicide or a violent crime is to degrade myself.

Fox News' Chris Wallace on Hugh Hewitt's Saturday radio program:

But what the FBI memo alleges, and it is an allegation, is, you know, would be considered a day at the beach in the Soviet gulag or Nazi...I mean, what was so horrific in the memo, and I'm not saying, you know, there aren't legitimate questions there, is that someone is chained to a floor and forced to defecate on themselves, and has loud rock music playing. Excuse me? I mean, you know, Auschwitz? Bergen Belsen? The Soviet gulag? I think they would have been very happy to be allowed to defecate on themselves.

Fox News' Chris Wallace on Hugh Hewitt's Saturday radio program:

But what the FBI memo alleges, and it is an allegation, is, you know, would be considered a day at the beach in the Soviet gulag or Nazi...I mean, what was so horrific in the memo, and I'm not saying, you know, there aren't legitimate questions there, is that someone is chained to a floor and forced to defecate on themselves, and has loud rock music playing. Excuse me? I mean, you know, Auschwitz? Bergen Belsen? The Soviet gulag? I think they would have been very happy to be allowed to defecate on themselves.

Friday, June 17, 2005

Bill Moyers: Anti-christ

I gather that some readers of this blog are regular listeners and viewers of public broadcasting. Surprise! In case you haven't heard already, you're about to get fucked:

Read more about it here.

Find out what to do about it here.

Yesterday, the House Appropriations Committee voted to drastically cut funding to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. CPB is the US-tax payer funded agency that passes funds to public broadcasting stations in this country. The proposal to cut funding was authored by Ohio Republican Representative Ralph Regula and would eliminate $100 million in federal funding to CPB, 25% of the total allocation. Regula's proposal also calls for all federal funding to the CPB to be eliminated in two years. The cuts, if passed, would represent the most drastic cutback of public broadcasting since Congress created the nonprofit CPB in 1967.

Read more about it here.

Find out what to do about it here.

Thursday, June 16, 2005

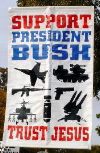

On fascism and debased religion

The American philosopher Stanley Cavell said in 1985 that the Republican right-wing's entertainment of a possible equation between nuclear war and a divinely redemptive apocalypse was in reality a symptom of nihilistic despair. Reagan and his men could find nothing in this world worth loving, so their idea of redemption could only be total annihilation. This analysis of course applies, in spades, to today's religious fascists.

But it is important not to conclude from this analysis that the only alternative to religious fascism is a completely secular vision of human life which holds no place for an afterlife. Modern (therefore liberal) existential philosophy betrays the same despair when it insists that death is absolutely "other" than human life, that it is an inconceivable realm of non-being that shadows the human world.

The realm of death must be filled with images for human life to have any meaning. These images must be somehow connected to human life, even as they point beyond it. A non-despairing vision of the afterlife will find things worth cherishing in this life and project them into the beyond. This projection will transform worthwhile human practices into ideal images that realize and fulfill the best potentials of human life. The idea of fulfillment is essential here. As Jesus said, "Think not that I have come to destroy the law and the prophets; I have come not to destroy but to fulfill."

The notion of a complete fulfillment of human potential allows for the afterlife to remain unknown, though at the same time, in some difficult way, imaginable. It thereby calls attention to, and facilitates the preservation of, the best of human life. And it also, by projecting these earthly practices into the beyond, where they are both eternalized and mysteriously extended, gives these practices an unfathomable depth of meaning. The best human practices are seen as worth as preserving, and as the manifestations of an ideal possibility that always demands further realization. An example from Christian theology (also used by Hegel as the image of the Spirit's perfect realization) is the image of the eternal banquet. We share food with each other here on earth, but the most joyful sharing only foreshadows a perfect feast, at which all of humanity is included and in which the pleasure of everyone is entirely mutual and reciprocal. The connection of the earthly meal with the eternal feast projects our minds hopefully into the future, but it also enhances the pleasure we take as we eat together in the present--our mutual sharing seems to participate in a cosmic reciprocity.

This sort of imagery retains its significance only if we always recognize the eternal difference between the image of the future and the reality of the present. The present partakes of the future, and is thus given meaning by it; but the future always remains to be realized, and so the future's perfection of the present remains imaginable but not thinkable or knowable. We can say, in simpler terms, that the image of the afterlife is an ideal that governs our thoughts here and now, but that can never in itself be seen clearly or rendered concrete on earth. Life participates in the afterlife, even as it remains inconceivably different from it. It is this simultaneous connection and differentiation between life and afterlife that gives life its fathomless and beautiful depth.

The modern philosophical vision of death as radically "other" is a symptom of modern despair. But it is only a secondary symptom, a reflection of the terrible evacuation of meaning from all conventional religious imagery. Who is responsible for this evacuation? Literal-minded, falsely religious fundmentalists (the perverters of the Reformation). Unlike the authentically religious, who remember and even wonder in joy at the inconceivable difference between reality and image, life and afterlife, prophecy and fulfillment, literal-minded fundamentalists insist on the reality of images that are only meant to suggest the inconceivable participation of the present in an ultimate eternity.

The fundamentalists tear these images away from the dark, unknown background that gives them their radiant aura, and they insert them grotesquely into the language of reality. In this context, the images seem absurd, infantile, caricatural sketches of base fantasies. The power of these images--their prophecy of a future that remains unknown, their endowment of earthly experience with a depth that remains unfathomed--is brutally destroyed. The fundamentalist use of apocalyptic imagery to discuss the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is only one of the most obvious examples of this process.

The late philosopher Gillian Rose has called attention to a passage in Walter Benjamin's book about 17th-century baroque allegory that describes this process in terrifying terms. Benjamin suggests that baroque imagery of the afterlife--hyper-ornate, grotesquely literal, frighteningly profuse--empties heaven and turns it into the void feared by modern philosophers:

"The baroque knows no eschatology...no mechanism by which all earthly things are gathered in together and exalted before being consigned to their end. The hereafter is emptied of everything which contains the slightest breath of this world, and from it the baroque extracts a profusion of things which customarily escaped the grasp of artistic formulation and, at its high points, brings them violently into the light of day, in order to clear an ultimate heaven, enabling it, as a vacuum, one day to destroy the world with catastrophic violence."

Now high baroque art is of course serious and important, and is far more meaningful than Tim La Haye's fantasies about the rapture or than Mohammed Atta's fantasies about having sex for all eternity with a harem of virgins. But the baroque and modern fundamentalism are related, in that even though both visions seem to be concerned with making the afterlife more real, more vivid, they are actually concerned with evacuating the afterlife of any connection to this life. This nihilistic, despairing, destructive evacuation is their true purpose. They pull from the afterlife as much as they can into the light of day, where it seems distorted and grotesque, as it does not belong here. What is left is the void, which is only related to this world as its catastrophic negation. Mohammed Atta could not have really "believed" that he would spend eternity with his harem, and Tim La Haye cannot really "believe" that heaven is his TV room after the dark races outside the door have been exterminated. He may think that this is what he believes, but it is not. These are not images of an afterlife, but mere signifiers of this world's total destruction.

The world after the apocalypse is not this one, and this negation is all that matters to today's religious fundamentalists, who are, in the end, nothing more than vicious nihilists.

But it is important not to conclude from this analysis that the only alternative to religious fascism is a completely secular vision of human life which holds no place for an afterlife. Modern (therefore liberal) existential philosophy betrays the same despair when it insists that death is absolutely "other" than human life, that it is an inconceivable realm of non-being that shadows the human world.

The realm of death must be filled with images for human life to have any meaning. These images must be somehow connected to human life, even as they point beyond it. A non-despairing vision of the afterlife will find things worth cherishing in this life and project them into the beyond. This projection will transform worthwhile human practices into ideal images that realize and fulfill the best potentials of human life. The idea of fulfillment is essential here. As Jesus said, "Think not that I have come to destroy the law and the prophets; I have come not to destroy but to fulfill."

The notion of a complete fulfillment of human potential allows for the afterlife to remain unknown, though at the same time, in some difficult way, imaginable. It thereby calls attention to, and facilitates the preservation of, the best of human life. And it also, by projecting these earthly practices into the beyond, where they are both eternalized and mysteriously extended, gives these practices an unfathomable depth of meaning. The best human practices are seen as worth as preserving, and as the manifestations of an ideal possibility that always demands further realization. An example from Christian theology (also used by Hegel as the image of the Spirit's perfect realization) is the image of the eternal banquet. We share food with each other here on earth, but the most joyful sharing only foreshadows a perfect feast, at which all of humanity is included and in which the pleasure of everyone is entirely mutual and reciprocal. The connection of the earthly meal with the eternal feast projects our minds hopefully into the future, but it also enhances the pleasure we take as we eat together in the present--our mutual sharing seems to participate in a cosmic reciprocity.

This sort of imagery retains its significance only if we always recognize the eternal difference between the image of the future and the reality of the present. The present partakes of the future, and is thus given meaning by it; but the future always remains to be realized, and so the future's perfection of the present remains imaginable but not thinkable or knowable. We can say, in simpler terms, that the image of the afterlife is an ideal that governs our thoughts here and now, but that can never in itself be seen clearly or rendered concrete on earth. Life participates in the afterlife, even as it remains inconceivably different from it. It is this simultaneous connection and differentiation between life and afterlife that gives life its fathomless and beautiful depth.

The modern philosophical vision of death as radically "other" is a symptom of modern despair. But it is only a secondary symptom, a reflection of the terrible evacuation of meaning from all conventional religious imagery. Who is responsible for this evacuation? Literal-minded, falsely religious fundmentalists (the perverters of the Reformation). Unlike the authentically religious, who remember and even wonder in joy at the inconceivable difference between reality and image, life and afterlife, prophecy and fulfillment, literal-minded fundamentalists insist on the reality of images that are only meant to suggest the inconceivable participation of the present in an ultimate eternity.

The fundamentalists tear these images away from the dark, unknown background that gives them their radiant aura, and they insert them grotesquely into the language of reality. In this context, the images seem absurd, infantile, caricatural sketches of base fantasies. The power of these images--their prophecy of a future that remains unknown, their endowment of earthly experience with a depth that remains unfathomed--is brutally destroyed. The fundamentalist use of apocalyptic imagery to discuss the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is only one of the most obvious examples of this process.

The late philosopher Gillian Rose has called attention to a passage in Walter Benjamin's book about 17th-century baroque allegory that describes this process in terrifying terms. Benjamin suggests that baroque imagery of the afterlife--hyper-ornate, grotesquely literal, frighteningly profuse--empties heaven and turns it into the void feared by modern philosophers:

"The baroque knows no eschatology...no mechanism by which all earthly things are gathered in together and exalted before being consigned to their end. The hereafter is emptied of everything which contains the slightest breath of this world, and from it the baroque extracts a profusion of things which customarily escaped the grasp of artistic formulation and, at its high points, brings them violently into the light of day, in order to clear an ultimate heaven, enabling it, as a vacuum, one day to destroy the world with catastrophic violence."

Now high baroque art is of course serious and important, and is far more meaningful than Tim La Haye's fantasies about the rapture or than Mohammed Atta's fantasies about having sex for all eternity with a harem of virgins. But the baroque and modern fundamentalism are related, in that even though both visions seem to be concerned with making the afterlife more real, more vivid, they are actually concerned with evacuating the afterlife of any connection to this life. This nihilistic, despairing, destructive evacuation is their true purpose. They pull from the afterlife as much as they can into the light of day, where it seems distorted and grotesque, as it does not belong here. What is left is the void, which is only related to this world as its catastrophic negation. Mohammed Atta could not have really "believed" that he would spend eternity with his harem, and Tim La Haye cannot really "believe" that heaven is his TV room after the dark races outside the door have been exterminated. He may think that this is what he believes, but it is not. These are not images of an afterlife, but mere signifiers of this world's total destruction.

The world after the apocalypse is not this one, and this negation is all that matters to today's religious fundamentalists, who are, in the end, nothing more than vicious nihilists.

Tuesday, June 14, 2005

Liberal State as New Moloch

Moloch was the god to whom the Canaanites sacrificed their children. The self-described "radically orthodox" theologian John Milbank sees the modern, secular, liberal state as an even more monstrous god, because it exacts more horrendous sacrifices, and does so in the name of nothing at all--nothing beyond the perpetuation of order, stability, and the meaningless "freedom" to not be killed.

Milbank contends that the secular state is in fact "sacralized," almost theocratic, in the way that it arrogates for itself--without its citizens seeing this as an action for which anyone is responsible--the authority to designate which individuals are actually human beings and which are outcast waste. (The "natural rights" of human beings can only be guaranteed by, and exercised within, the state, which thus becomes the source and arbiter of these "rights," which are not actually, and never were, "natural.") These and many related ideas are explored in Milbank's 2002 essay on "Sovereignty, Empire, Capital, and Terror." The main thesis is that catastrophic terrorism is not unique, except in the way that it challenges the sovereignty of the secular state. But Milbank has many other interesting things to say about contemporary geopolitics and neo-fascist dementia.

Milbank contends that the secular state is in fact "sacralized," almost theocratic, in the way that it arrogates for itself--without its citizens seeing this as an action for which anyone is responsible--the authority to designate which individuals are actually human beings and which are outcast waste. (The "natural rights" of human beings can only be guaranteed by, and exercised within, the state, which thus becomes the source and arbiter of these "rights," which are not actually, and never were, "natural.") These and many related ideas are explored in Milbank's 2002 essay on "Sovereignty, Empire, Capital, and Terror." The main thesis is that catastrophic terrorism is not unique, except in the way that it challenges the sovereignty of the secular state. But Milbank has many other interesting things to say about contemporary geopolitics and neo-fascist dementia.